Property 3 — Boundaries

Boundaries is introduced in

As elements of a form become more detailed, new elements grow within them. Forms increase in complexity by seeding from within. This naturally leads to some of these inner forms having very large boundaries. As the forms grow, their boundaries do not deteriorate, for they are part of why the inner form is successful. Instead, these large boundaries are reinforced and remain part of the overall compound.

There are always edges to things: where they end and the rest of their world begins. When objects have an inside and an outside, there is a literal boundary. These boundaries can be strong centres and have significant presence and scale.

When a contrast is jarring rather than complementary, it weakens the centres involved. To protect the centres from discord, we can introduce a boundary that works well with both sides of the divide.

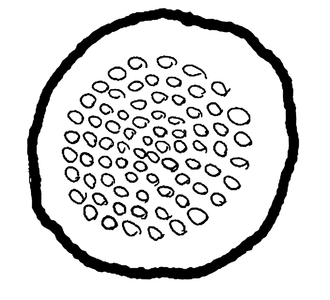

Some boundaries can be massive, almost as large as the thing they are bounding[NoO1-01]. They are not a thin line between things but can be thick like a moat or the margins of a book. They can be detailed, such as the dunes dividing a beach from the lands beyond or a brick wall surrounding the mouth of a well. They can be plain, such as the rim of a plate or the grounds around a building on a lawned campus.

They can be an absence, such as the solid material around the holes of a shower head. The boundary in the following image is not the thicker black line but the blank white gap between the outline and the detailed interior.

A boundary can be a conspicuous absence.

A boundary can be a conspicuous absence.

The value of boundaries can be how they extend the meaning of the separation while enhancing the visibility of the centre they surround. Boundaries can be around objects but also at the ends of linear things, such as columns or ropes.

The principle of boundaries is that they reinforce endings and divisions. In things that stop, they help recognise the termination and the preceding existence. Boundaries fulfil the need to say something about the differences between things while recognising the value in their presence.

Without boundaries, colours merge, and ends seem unfinished. Weak contrasts start to show as a failure to differentiate rather than an attempt to include.

Boundaries are places for details to be added without making space for them artificially. Fences or colonnades, patterns around a form, details in a design surrounding an emptiness; they all make good boundaries that reinforce and contrast.

I believe a boundary helps a contrast fit with its surroundings. If something is too dark, detailed, or colourful, a good boundary can provide the distance to smooth the transition. I have edited the image of the door on the right to show how it looks weaker and out of place when it lacks a border.

Christopher Alexander used an example of a Gothic door. I replicate the example here with a different image of a door and an alteration to remove the surround, showing the impact of not having the necessary framing.

A boundary can help a contrast fit.

A boundary can help a contrast fit.

Boundaries can be cell walls or rivers used as borders of countries. Boundaries protect a centre from the world outside. So, a line is not a boundary. Because without thickness, a boundary cannot protect.

So, although hairlines can indicate the location of a boundary, the true centre is the boundary extending to the white space above and below the line. The boundary is the whole form, the gap-line-gap sequence.

In books, some publishers aren’t aware of the importance of margins and push the text of a book out to the edges of the pages. Leaving a tiny gap for a border feels like a poorly framed centre on every page.

When I first learnt about typography and book layout, I did not understand why the inner margin can often be smaller than the outer, but now I see it as a way to emphasise the boundary around the two-page spread. The inner margin handles the fold and not much else. The outer margin is a companion to the top and bottom margin, not the inner. Boundaries are, therefore, contextual to where they are embedded.