Property 7 — Local Symmetries

Local Symmetries is introduced in

This property refers to not just symmetry but overlapping and interweaving symmetries. Snowflakes and other self-similar shapes have something like this, but local symmetries do not require a fractal nature. Instead, think only of the idea that the repetition is a repetition of something made up of something with repetitions.

Rather than start with something lacking symmetries, this property emerges from how unfolding processes operate. We don’t often repair a form back to having local symmetries, as they naturally arise from splitting, repeating, or using symmetry to reinforce structures.

Partitioning and duplicating while mirroring or adjusting based on steps leads to this hierarchical repetition:

AA BBB AAA BBB AA CCCC AA BBB AAA BBB AA

A strong pattern is present there, but it’s not entirely self-similar. We needn’t be too strict about the facets either. This is cadence, poetic flow, and verse structure as much as mirroring or symmetry. Pleasant songs tend to have repetition at all different scales, and poems will have self-referential structural symmetry. Although a book of prose is unlikely to have much local symmetry, the left–right of the pages maintains at least a simple local continuity.

A terraced street will have symmetries[NoO1-01] in the row of houses. Even if each home has been made individual by its inhabitants, the alternating left–right door placement reinforces local symmetry. Other, smaller symmetries strengthen it further. The placement of windows and even the windowpanes and roof tiles deepen the character of the houses. It all adds up to a pleasing sequence along the whole street. The same is often true of any main market street with symmetric arrangements of roads, shops, frontages, and arcades with columns. Even the cobbles or paving slabs add to local symmetry. When you last walked along a solid and continuous poured concrete walkway, how did it feel compared to paving slabs or cobbles?

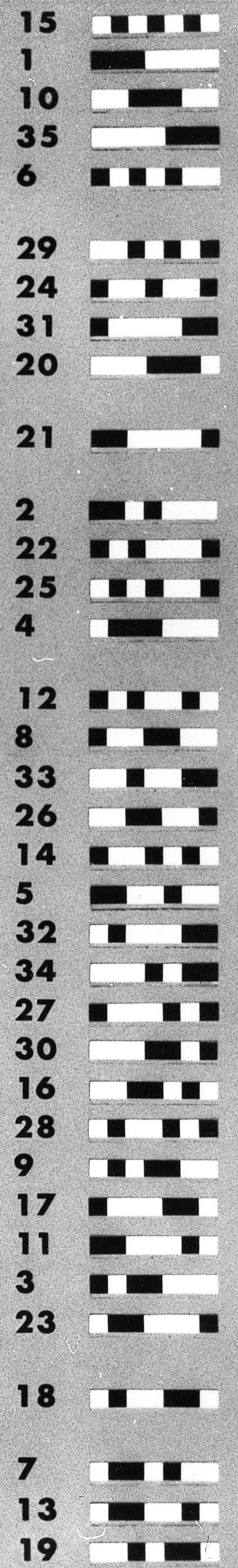

This property was proven in a series of abstract tests often referred to as the paper strip experiment. The 35 strips had all the possible permutations of three black squares on a strip seven squares long. Participants in the study were tasked with different tests to find an order to the strips according to how orderly, coherent, or simple they were. Though the test results differed, they were statistically similar.

Christopher Alexander collected the results and spent much time attempting to find the rationalisation for the order. Inspiration struck after some years when he considered local symmetries. He had been stuck on the idea of clumps and overall symmetry and had not considered how vital the sub-symmetries were. Calculating the score of the strips counting every symmetry, even those where the colours do not change, suddenly showed a very strong correlation to the ordering.

When biasing for longer, larger symmetric sequences, it seemed the correlation worsened. It proved to him that the number of symmetries was the most significant, not their size. The symmetries and sub-symmetries are the significant parts of the property.

The strip experiment and local symmetries in general can be considered to suggest the property is fundamentally about information density. Good forms are easily recognised. Ease of recognition comes from having patterns that match our preconceptions. Local symmetries give us something to latch onto. We can take one element of a scene and project it onto another as only a small piece of information—the duplication or mirroring of another element. We pattern match all the time, and the less pattern we can match the greater the cognitive load when trying to understand the whole—the more individual elements we have to concentrate on as we think about the compound form.

— Christopher Alexander, The Center for Environmental Structure,

The Nature of Order, Book 1 [NoO1-01], p. 189.

This parallels what we consider to be a natural unfolding. DNA works by a small number of rules, so there will be symmetries as every non-symmetric element is information and there’s only so much information in DNA. Our sense of what is good will be tuned to look for things with this quality of similarity of element.

When we see a lot of detail with many different ideas it either captivates through curiosity or repulses us with its vulgarity. Almost everything we consider beautiful is simple in this respect. Therefore, wholesome forms present otherwise complicated looking forms through repetition with any variation only present when it is of vital importance.